"Não sou imparcial em relação à Europa e, como os milhares que marcharam ontem, não pretendo fingir o que não sou. Goste ou não, e eu gosto, sou europeu. Eu também sou britânico, britânico e europeu. Como muitos milhões em toda a Grã-Bretanha e Europa, o DNA da minha família é uma mistura muito interessante. Somos ingleses, belgas, alemães, franceses, holandeses, croatas, galeses, escoceses e romenos. Eu moro em um país onde a família real tem origem em literalmente dezenas de países europeus. Eles são tão europeus quanto qualquer um de nós e mais do que a maioria de nós."

"Não sou imparcial em relação à Europa e, como os milhares que marcharam ontem, não pretendo fingir o que não sou. Goste ou não, e eu gosto, sou europeu. Eu também sou britânico, britânico e europeu. Como muitos milhões em toda a Grã-Bretanha e Europa, o DNA da minha família é uma mistura muito interessante. Somos ingleses, belgas, alemães, franceses, holandeses, croatas, galeses, escoceses e romenos. Eu moro em um país onde a família real tem origem em literalmente dezenas de países europeus. Eles são tão europeus quanto qualquer um de nós e mais do que a maioria de nós."

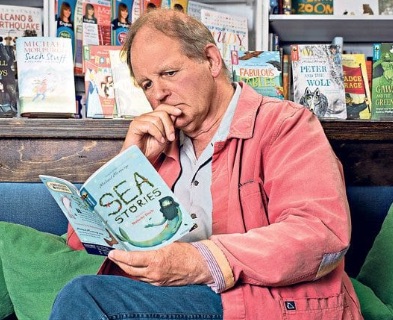

Na iminência de sair da União Europeia, a Grã-Bretanha está dividida. Com paixões dos dois lados vindo à tona, porque os britânicos sabem que estão numa encruzilhada muito difícil, onde o Reino Unido chegou por um erro político. É um caminho que parece sem volta. Mesmo reconhecendo alguns argumentos muito fortes para esse divórcio, eles sabem que a saída da União Europeia terá um preço muito alto e amargo. Vale a pena ler o desabafo do escritor britânido Michael Morpurgo, publicado no Sunday Times, de domingo, 20 de outubro.

"Nossa língua, sem dúvida a jóia de nossa cultura, é uma língua mestiça, uma mistura magnífica de todas as ilhas britânicas e de toda a Europa também - de, entre outras: Escandinávia, Itália e Grécia, da França e da Alemanha. Nossas leis e nossa religião primitiva têm suas bases em Roma, nossa democracia em Atenas. Portanto, não precisamos de uma bandeira, hino ou mesmo uma união para ser europeu. Nós somos europeus. Compartilhamos a história da Europa, sua cultura, seu aprendizado, suas glórias e suas vergonhas.

"Ao longo dos séculos, fomos aliados, inimigos e aliados novamente, muitas vezes, com quase todos os países da Europa. Todos nós fizemos guerra até a morte, sem dúvida o continente mais beligerante e destrutivo do mundo. Se temos uma falha fatal, é que os estados-nação da Europa recorrem com muita frequência a brigas e lutas para resolver problemas. A Grã-Bretanha fez sua parte, sendo muito europeia nesse sentido. Como todos os outros países da Europa, invadimos e fomos invadidos. Conhecemos a exultação da vitória e a humilhação da derrota. E nós conhecemos a perda e o sofrimento.

"Somente na segunda metade do século XX fez-se essa mudança. Construímos um túnel: ingressamos na Europa fisicamente. E nos juntamos à Europa politicamente. Juntamos negócios, para acordos comerciais.

"No entanto, como países em todos os lugares, conhecemos e entendemos muito pouco da história de outros. Cada um de nós vê o mundo através de nosso próprio prisma. Ou não percebemos ou esquecemos a razão pela qual a União Europeia, a Comunidade Europeia, o Mercado Comum surgiram e quem os criou. Uma fênix da paz, inspirada por grandes e boas pessoas, erguia-se das cinzas das ruínas de uma Europa que havia se envolvido duas vezes nas mais terríveis guerras que o mundo já conheceu.

"Três anos atrás, o governo conservador decidiu, por suas próprias razões políticas, realizar um referendo. Esperava vencer. Isso não aconteceu.

"Não se percebeu o quão alienados, ameaçados e ressentidos muitos milhões de nossos cidadãos estavam se sentindo. Eles estavam se sentindo deixados de fora, no frio, abandonados, ignorados. Como de fato têm sido por décadas. No referendo, a Europa assumiu toda a culpa. E alguma culpa foi justificada. A divisão entre quem tem e quem não tem é vergonhosamente ampla neste país e em toda a Europa. A Europa comandou isso, motivada por um desejo de prosperidade que não foi suficientemente inclusivo. A ascensão do nacionalismo populista comum a todos os estados europeus não é por acaso, não é coincidência. É mais uma consequência de um sistema que favorece aqueles que emplumam seus próprios ninhos, em vez de criar sociedades onde os benefícios são compartilhados de forma mais equitativa. A União Europeia esqueceu suas raízes, a verdadeira razão de sua existência.

"Era natural o suficiente para a Grã-Bretanha, o menos comprometido dos países europeus, ser o primeiro a se afastar. Podemos não ser os últimos. Continue como estamos e as coisas vão desmoronar: o centro não se sustentará. A Europa - com a Grã-Bretanha ainda um membro, que é minha fervorosa esperança - tem que se lembrar de sua história, se reinventar, se reformar para sobreviver. É uma reunião voluntária de nações livres e democráticas. Se, no coração da Europa, a democracia está comprometida - e atualmente está -, a Europa falhará e deveria falhar.

"Se a Europa morrer, a prosperidade morrerá e nossa paz abençoada morrerá com ela. Não devemos deixar isso acontecer. Eu não quero o divórcio. Não quero me afastar da Europa. A Europa pode ser uma família defeituosa, mas é minha família. Todos os casamentos e parcerias devem ter um esforço de realização. E quero que nós na Grã-Bretanha fiquemos e ajudemos a concretizar isso."

Foto: Andrew Crowlevy: The Telegraph.

Tradução: João José Forni.

Leia o original em inglês

I don't want a divorce. I don't want to be estranged. Europe is my family.

I am not impartial about Europe and, like the thousands who marched yesterday, will not pretend I am. Like it or not, and I do like it, I am European. I am British too, British and European. As with many millions all over Britain and Europe, the DNA of my family is a most interesting mix. We are English, Belgian, German, French, Dutch, Croatian, Welsh, Scottish and Romanian. I live in a country where the royal family has its origins in literally dozens of European countries. They are as European as any of us, and more so than most of us.

Our language, arguably the jewel of our culture, is a mongrel language, a magnificent blend, from all over the British Isles and all over Europe too — from, among others: Scandinavia, Italy and Greece, from France and Germany. Our laws and our early religion have their foundations in Rome, our democracy in Athens. So we do not need a flag or anthem or even a union to be European. We are European. We share Europe’s history, her culture, her learning, her glories and her shames.

Over the centuries we have been allies, then enemies, then allies again, many times over, with just about every country in Europe. We have all done war to death, arguably the most belligerent and destructive continent on this earth. If we have one fatal flaw, it is that the nation states of Europe all too often resort to squabbling and fighting to solve problems. Britain has done its share, been very European in this regard. Like all other countries in Europe, we have invaded and been invaded. We have known the exultation of victory and the humiliation of defeat. And we have known the loss and suffering.

Only in the second half of the 20th century did this change. We built a tunnel: we joined Europe physically. And we joined Europe politically. We joined for business, for trade deals.

Yet, like countries everywhere, we know and understand very little of the history of others. We each see the world through our own prism. We either did not realise or we forgot the reason the EU, the European Community, the Common Market, came into existence and who had created it. A phoenix of peace, inspired by great and good people, was rising from the ashes of the ruins of a Europe that had twice embroiled itself in the most terrible wars the world had ever known.

Three years ago the Conservative government decided, for its own political reasons, to hold a referendum. It expected to win. It did not.

It seemed unaware how alienated and threatened and resentful so many millions of our citizens were feeling. They were feeling left out in the cold, abandoned, ignored. As indeed they have been for decades. In the referendum Europe took the whole blame. And some blame was justified. The divide between those who have and those who have not is shamefully wide in this country and wide all over Europe. Europe has presided over this, driven as it is by a desire for prosperity that has not been nearly inclusive enough. The rise of populist nationalism common to all European states is no accident, no coincidence. It is rather a consequence of a system that favours those who feather their own nests, rather than creating societies where benefits are more equitably shared. The EU has forgotten its roots, the real reason for its existence.

It was natural enough for Britain, the least committed of the European countries, to be the first to break away. We may not be the last. Go on as we are and things will fall apart: the centre will not hold. Europe — with Britain still a member, which is my fervent hope — has to remember its history, reinvent itself, reform itself if it is to survive. It is a voluntary gathering of free and democratic nations. If, at the heart of Europe, democracy is compromised — and at present it is — then Europe will fail, and should fail.

If Europe dies, then prosperity will die, and our blessed peace will die with it. We must not let that happen. I don’t want a divorce. I do not want to be estranged from Europe. Europe may be a flawed family but it’s my family. All marriages and partnerships have to be worked at. And I want us in Britain to stay and help make it work.

I am not impartial about Europe and, like the thousands who marched yesterday, will not pretend I am. Like it or not, and I do like it, I am European. I am British too, British and European. As with many millions all over Britain and Europe, the DNA of my family is a most interesting mix. We are English, Belgian, German, French, Dutch, Croatian, Welsh, Scottish and Romanian. I live in a country where the royal family has its origins in literally dozens of European countries. They are as European as any of us, and more so than most of us.

Our language, arguably the jewel of our culture, is a mongrel language, a magnificent blend, from all over the British Isles and all over Europe too — from, among others: Scandinavia, Italy and Greece, from France and Germany. Our laws and our early religion have their foundations in Rome, our democracy in Athens. So we do not need a flag or anthem or even a union to be European. We are European. We share Europe’s history, her culture, her learning, her glories and her shames.

Over the centuries we have been allies, then enemies, then allies again, many times over, with just about every country in Europe. We have all done war to death, arguably the most belligerent and destructive continent on this earth. If we have one fatal flaw, it is that the nation states of Europe all too often resort to squabbling and fighting to solve problems. Britain has done its share, been very European in this regard. Like all other countries in Europe, we have invaded and been invaded. We have known the exultation of victory and the humiliation of defeat. And we have known the loss and suffering.

Only in the second half of the 20th century did this change. We built a tunnel: we joined Europe physically. And we joined Europe politically. We joined for business, for trade deals.

Yet, like countries everywhere, we know and understand very little of the history of others. We each see the world through our own prism. We either did not realise or we forgot the reason the EU, the European Community, the Common Market, came into existence and who had created it. A phoenix of peace, inspired by great and good people, was rising from the ashes of the ruins of a Europe that had twice embroiled itself in the most terrible wars the world had ever known.

Three years ago the Conservative government decided, for its own political reasons, to hold a referendum. It expected to win. It did not.

It seemed unaware how alienated and threatened and resentful so many millions of our citizens were feeling. They were feeling left out in the cold, abandoned, ignored. As indeed they have been for decades. In the referendum Europe took the whole blame. And some blame was justified. The divide between those who have and those who have not is shamefully wide in this country and wide all over Europe. Europe has presided over this, driven as it is by a desire for prosperity that has not been nearly inclusive enough. The rise of populist nationalism common to all European states is no accident, no coincidence. It is rather a consequence of a system that favours those who feather their own nests, rather than creating societies where benefits are more equitably shared. The EU has forgotten its roots, the real reason for its existence.

It was natural enough for Britain, the least committed of the European countries, to be the first to break away. We may not be the last. Go on as we are and things will fall apart: the centre will not hold. Europe — with Britain still a member, which is my fervent hope — has to remember its history, reinvent itself, reform itself if it is to survive. It is a voluntary gathering of free and democratic nations. If, at the heart of Europe, democracy is compromised — and at present it is — then Europe will fail, and should fail.

If Europe dies, then prosperity will die, and our blessed peace will die with it. We must not let that happen. I don’t want a divorce. I do not want to be estranged from Europe. Europe may be a flawed family but it’s my family. All marriages and partnerships have to be worked at. And I want us in Britain to stay and help make it work.

*Michael Morpurgo is a former children’s laureate. His latest book is Boy Giant: Son of Gulliver (HarperCollins Children’s Books, £12.99)